Bromley Hall evolution

This article originally appeared in Context 95, published by The Institute of Historic Building Conservation in July 2006. It was written by Paul Latham.

An historic building’s evolution can be illuminated by a considered approach to its conservation and presentation.

[Image: The west front after conservation work}

Bromley Hall was built on the medieval walls of the moated Lower Manor of Bramberley in c1485-90 by Holy Trinity Priory, Aldgate, some 40 years before its dissolution. It is a unique monastic survival in the heavily industrialised landscape of East London. The priory granted the 30-year lease of the square brick building to the knight John Blount, a trusted member of Henry VIII’s inner circle and King’s Spear (or bodyguard) upon his accession in 1509. This tells us something of the purpose of the building. John’s daughter Elizabeth was to attract the king’s attention, and their subsequent affair led to the birth of Henry Fitzroy. The hall was lavishly built and richly furnished from evidence of tapestry hangings, suggesting its probable status as a house of pleasure for the king.

Henry VIII undertook major work following Blount’s death, and the surrender of the hall and other assets of the priory to the Crown in 1531-2. This included the replacement of a probable leaded and crenellated roof with a step-gabled garret stage, the addition of suspended timber ground floors over ceramic tiled finishes, and heating.

[Image: A possible reconstruction (by Paul Latham) of Bromley Hall after surrender to the Crown, c1531–2]

After use as a country lodge by the Crown for the remainder of the 16th century, the hall was purchased by Sir Arthur Ingram in 1606. Ingram was organiser and negotiator to Sir Robert Cecil, Lord Treasurer to James I. In this role he was engaged in the sale of Crown lands to syndicates of City merchants. No doubt he saw the hall as a valuable venue for his own entertaining, conveniently close to Greenwich Palace and the City. He had already acquired a number of country estates by offering credit to courtiers and subsequently manipulating their affairs to his own advantage. The hall was therefore not (nor could it have fulfilled the function of) his main residence.

|

|

[Image: An oak doorway of c1485–90 with carved spandrels of a hound and hind, before conservation work. A series of paint sequences survives from the 15th to 17th centuries. New chestnut lath and lime plaster was inserted in the right hand lower panel to protect a damaged section of daub.]

Probate records show that the hall was ‘newly built’ by 1625, probably by Ingram. Cartographic and archaeological evidence suggests this included the removal of the secondary north and south gables. Ownership by a number of wealthy city merchants followed in the 17th and 18th centuries. In 1710 William Woolley, goldsmith and citizen of London, raised a mortgage to remodel the attic storey, providing a four-sided steeply pitched roof with plaster coving in the fashionable Italian style. Ownership by a number of wealthy city merchants followed in the 17th and 18th centuries. In 1710 William Woolley, goldsmith and citizen of London, raised a mortgage to remodel the attic storey, providing a four-sided steeply pitched roof with plaster coving in the fashionable Italian style.

Since then the building has been continually updated, including a southern annexe extension in 1926 by the Royal College of St Katherine when the hall was used as an infant welfare centre. In the Second World War a bomb severely damaged the rear wall, which was subsequently renewed by the War Commission c1952.

This brief historical summary gives some background to the conservation and conversion of Bromley Hall (which The Regeneration Practice began in March 2005) to provide small offices for Leaside Regeneration. Our conservation philosophy included the usual good practice points, such as undoing inappropriate repairs; using appropriate materials; preserving and protecting as much of the old as possible; and integrating new services without damage. However, a multitude of hidden features discovered during the work posed significant dilemmas in the presentation of the project.

Given the significance of the early history, should we expose more of the Tudor work and risk an incoherent presentation? What about the client’s budget? Our starting point was to recognise the predominant architectural phase: the remodelled house by William Woolley c1710.

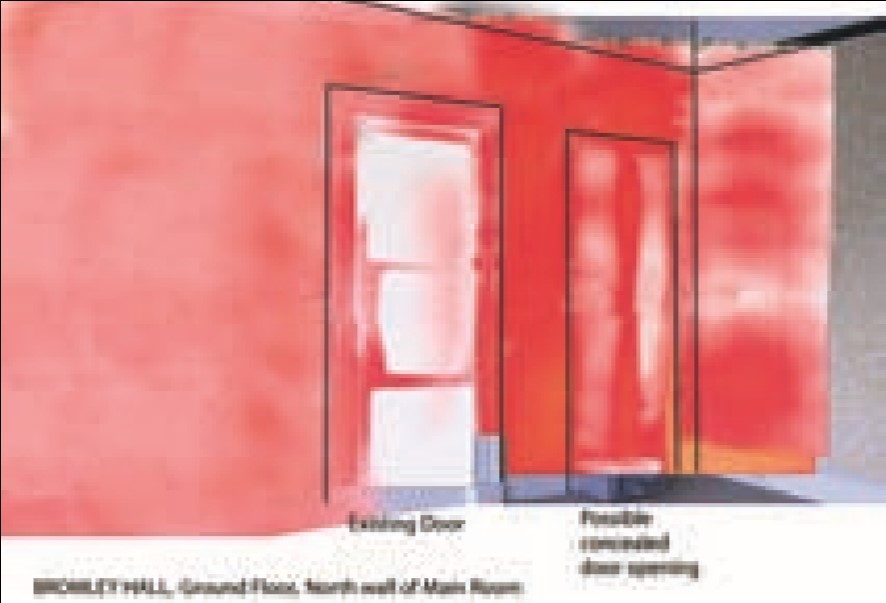

Some discoveries, like an oak doorway dating from the surrender of the building to Henry VIII, found by thermography, were carefully recorded by Pre-construct archaeology and covered up. Their exposure would undoubtedly confuse the presentation of Woolley’s (formerly) panelled ground floor room with its centrally placed, eight-panelled existing doorway. Another Tudor doorway discovered behind modern plasterboard in the hallway offered an opportunity to display a complete section of wall from the earliest phase.

|

|

[Image: A Tudor doorway discovered by thermographic study by Demaus Building Diagnostics]

The further discovery of a complete 15th century blocked window (including Baltic timber framing and brickwork of c1710) in the hallway told us of an important alteration in the internal layout by Woolley. At that date the southern river access was abandoned in favour of a new western doorway providing road access to London. All the Tudor windows were blocked or altered, and new sashes inserted in the north and west front. A series of paint sequences trapped inside and around the blocked window were conserved by our conservator Andrea Kirkham.

[Image: A 15th century window discovered in the hallway]

These discoveries provided an opportunity to present a complete section of wall as an ‘unconstructed ruin’. This shows how the developing road system contributed to the evolution of the building form and how the house was decorated during this transitional period.

[Image: A 15th century relieving arch and medieval walls of the Lower Manor of Bramberley displayed beneath a glass floor]

The remains of medieval walls found below the ground floor by the Museum of London archaeology Service told us the story of the pre-existing moated Lower Manor of Bramberley of c1255. These walls were conserved and displayed beneath a glass window in the floor.

One of our conservation philosophies at the outset of this project was to preserve and protect as much of the old as possible. Bromley Hall demonstrated to us how such a philosophy was at best only a starting point. In order to ensure that the display of hidden features added value to the understanding of the early history, while not detracting from a coherent presentation of the building as an 18th century house, different approaches needed to be tested in the learning environment of the project itself. The right approach in each case emerged after a step-by-step process involving the whole team and the statutory authorities in the decision.

Paul Latham is a director at The Regeneration Practice (TRP).

--Institute of Historic Building Conservation

Related articles on Designing Buildings Wiki

IHBC NewsBlog

SAVE celebrates 50 years of campaigning 1975-2025

SAVE Britain’s Heritage has announced events across the country to celebrate bringing new life to remarkable buildings.

IHBC Annual School 2025 - Shrewsbury 12-14 June

Themed Heritage in Context – Value: Plan: Change, join in-person or online.

200th Anniversary Celebration of the Modern Railway Planned

The Stockton & Darlington Railway opened on September 27, 1825.

Competence Framework Launched for Sustainability in the Built Environment

The Construction Industry Council (CIC) and the Edge have jointly published the framework.

Historic England Launches Wellbeing Strategy for Heritage

Whether through visiting, volunteering, learning or creative practice, engaging with heritage can strengthen confidence, resilience, hope and social connections.

National Trust for Canada’s Review of 2024

Great Saves & Worst Losses Highlighted

IHBC's SelfStarter Website Undergoes Refresh

New updates and resources for emerging conservation professionals.

‘Behind the Scenes’ podcast on St. Pauls Cathedral Published

Experience the inside track on one of the world’s best known places of worship and visitor attractions.

National Audit Office (NAO) says Government building maintenance backlog is at least £49 billion

The public spending watchdog will need to consider the best way to manage its assets to bring property condition to a satisfactory level.

IHBC Publishes C182 focused on Heating and Ventilation

The latest issue of Context explores sustainable heating for listed buildings and more.